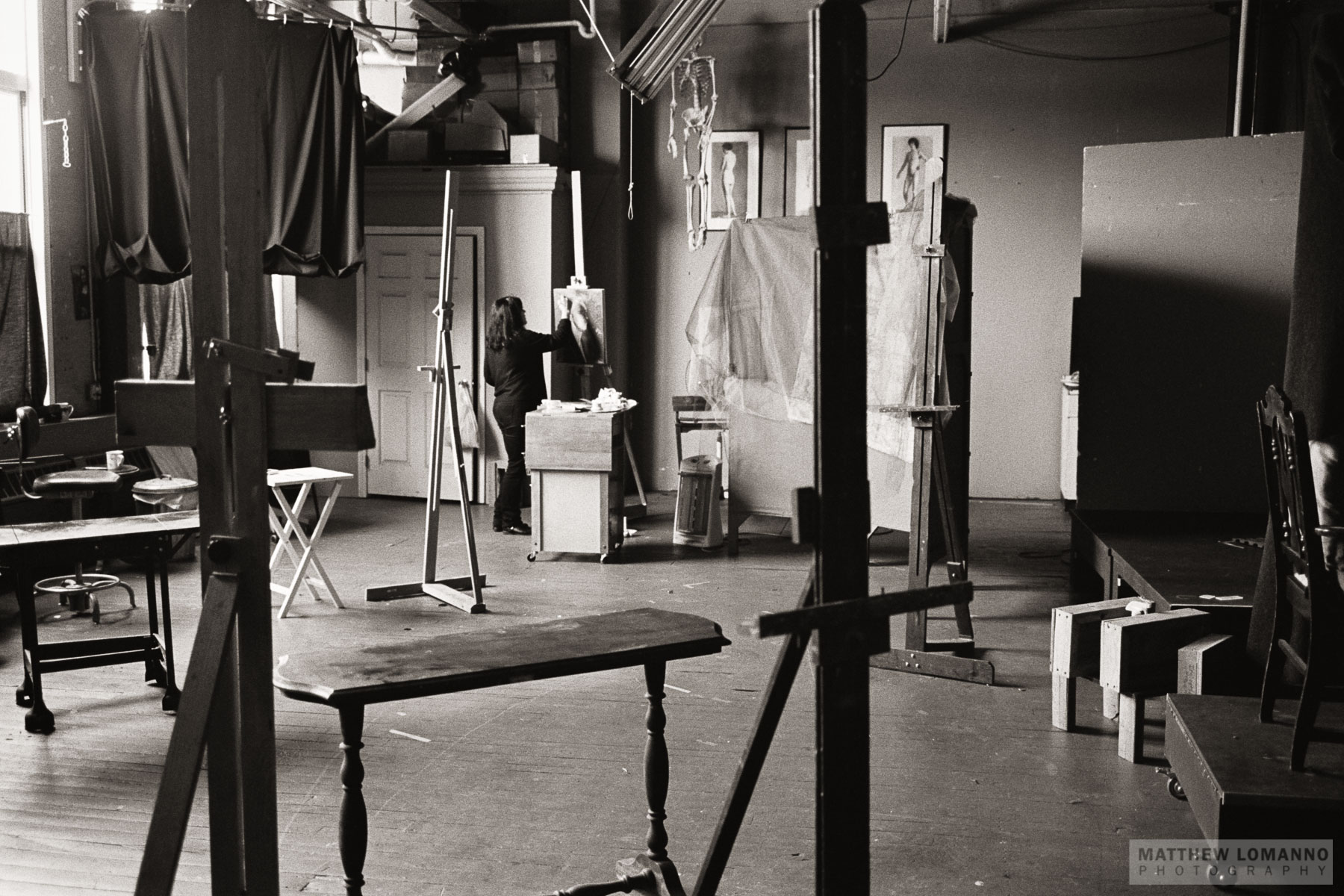

Last week was filled with preparation for—and participation in—ArtFront's inaugural 3-day pop-up art exhibit. I wrote about my involvement and the results, but now it was time to install the work. While a couple of us were hanging my 6-foot prints, Christina had a team to build structures for her chandeliers. I helped when I could, and I wasn't able to observe this process fully, but I made a few photos as they took form. When it was ready, Christina asked someone to document the "barn raising"; I was happy to oblige.

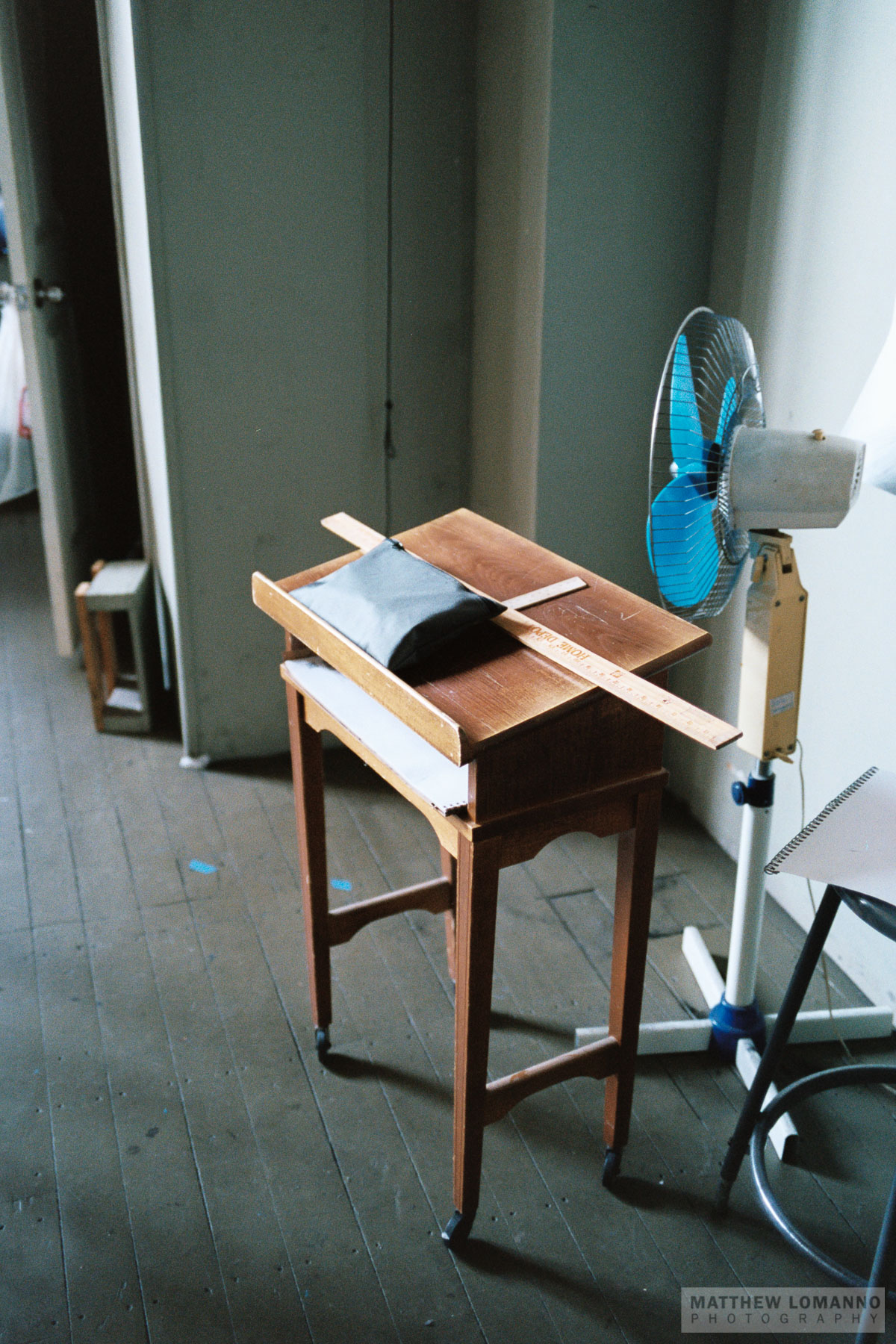

I posted the short set below on my Instagram feed the next day and, as we were at the exhibit every night, didn't think about it again until now. What I found intriguing especially was the process of building a structure to hold her artwork with pallets as the base and top. She and Vivian had a general plan, materials, and tools, but putting it together to make it functional and stable took a team effort with many attempts: how to anchor the 15-foot posts? these screws? no, try those; the palettes don't have enough depth, so add blocks to the middle of the pallets; we need to stabilize the outside further, so add these metal plates; et al.

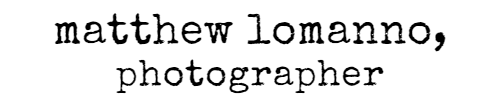

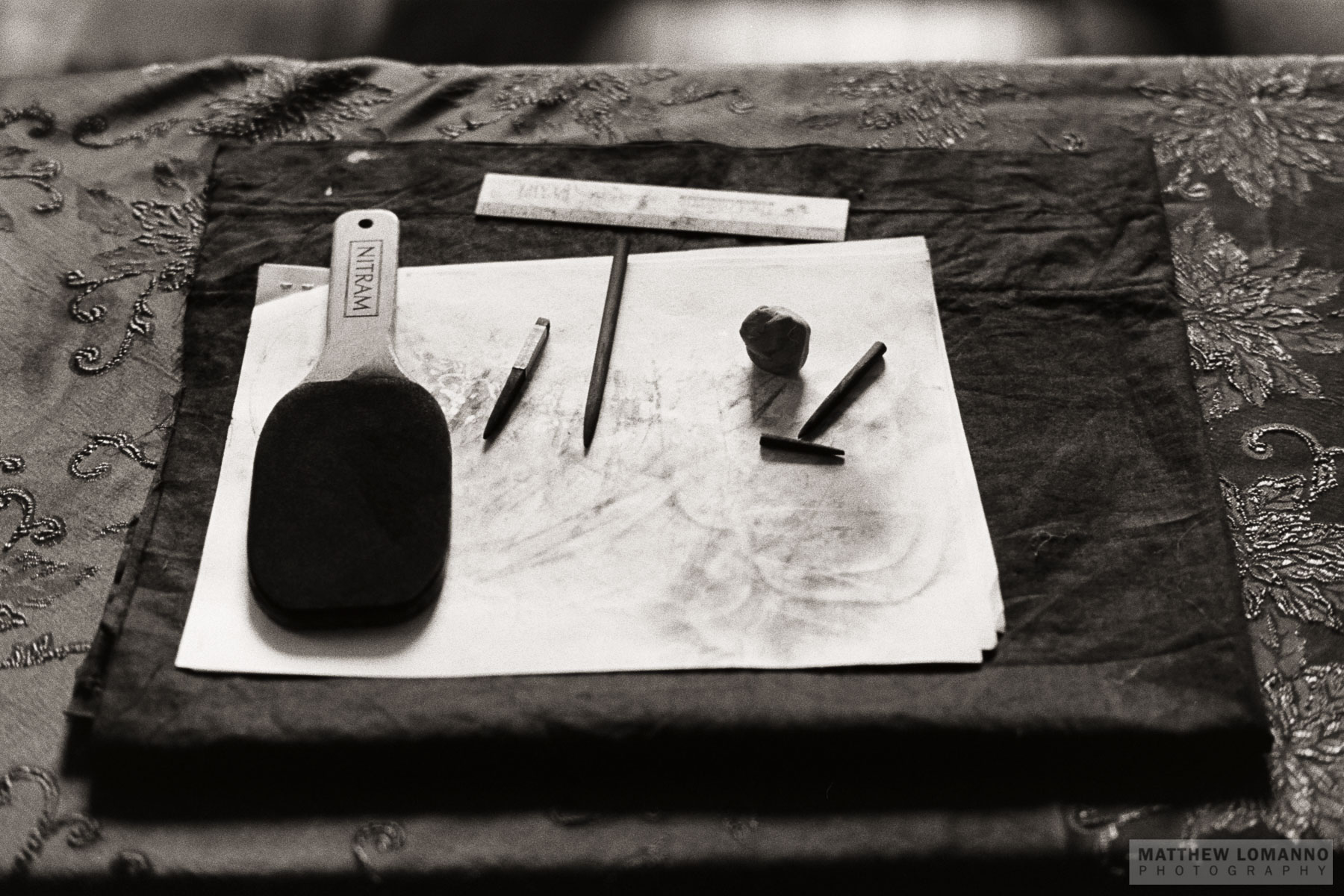

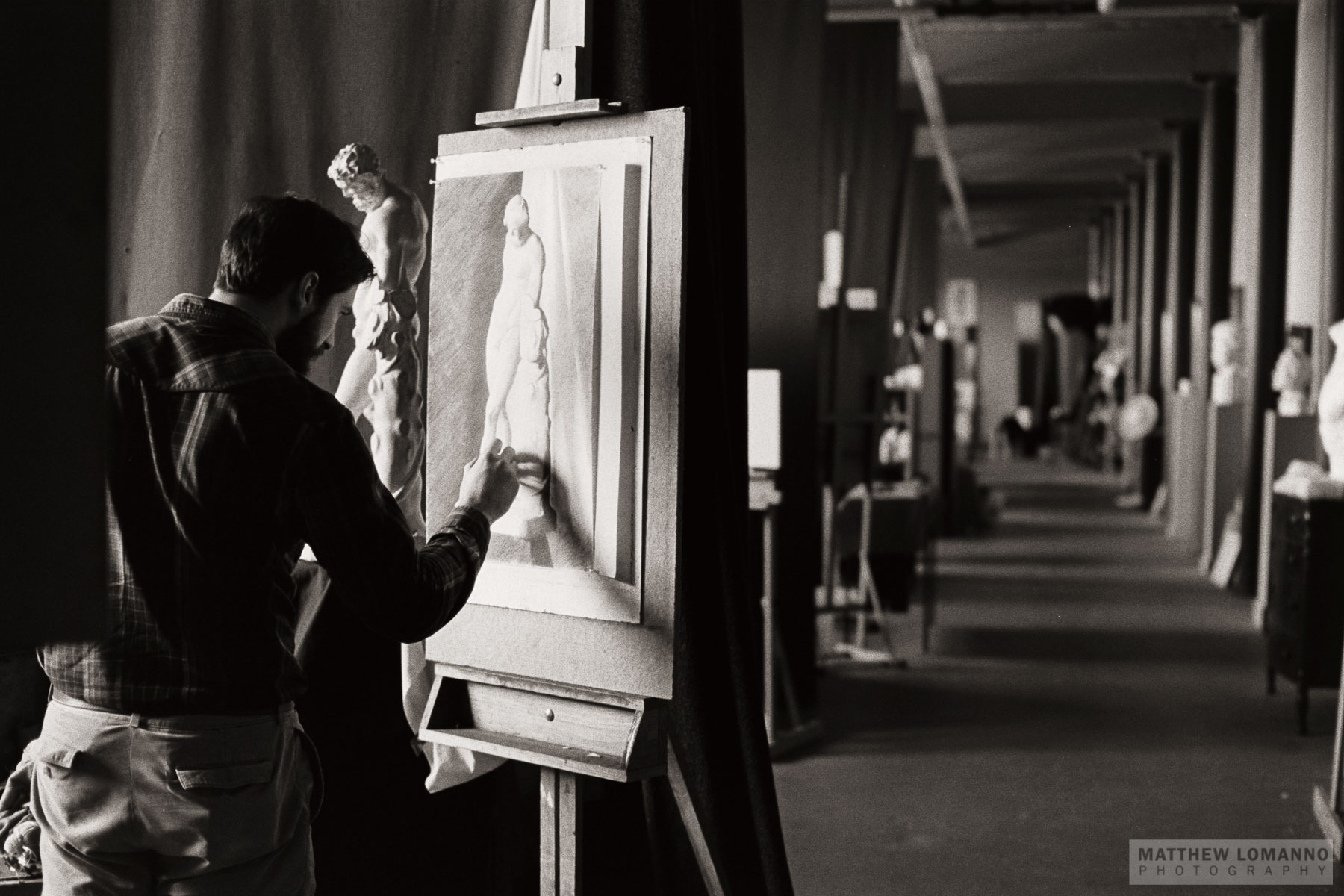

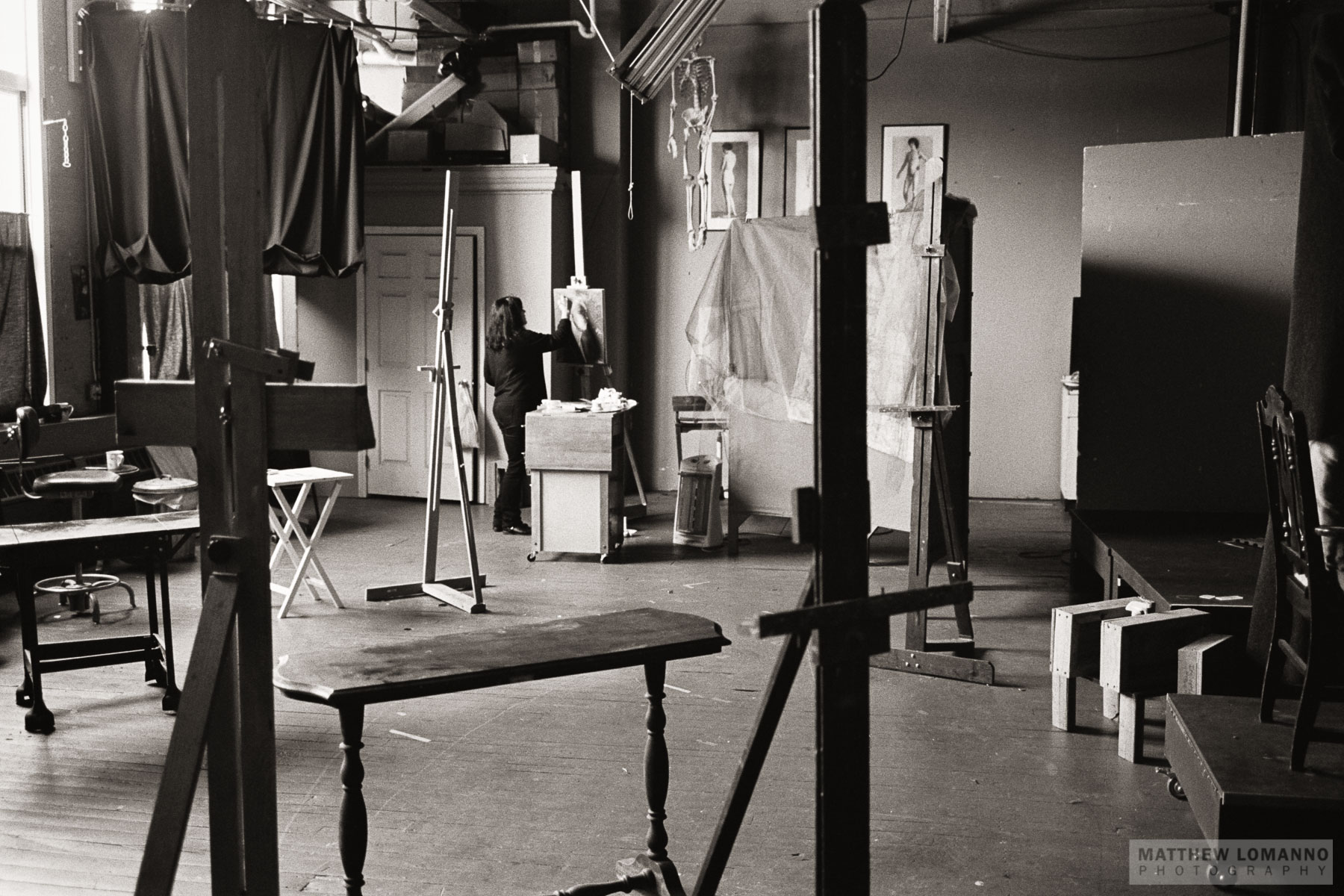

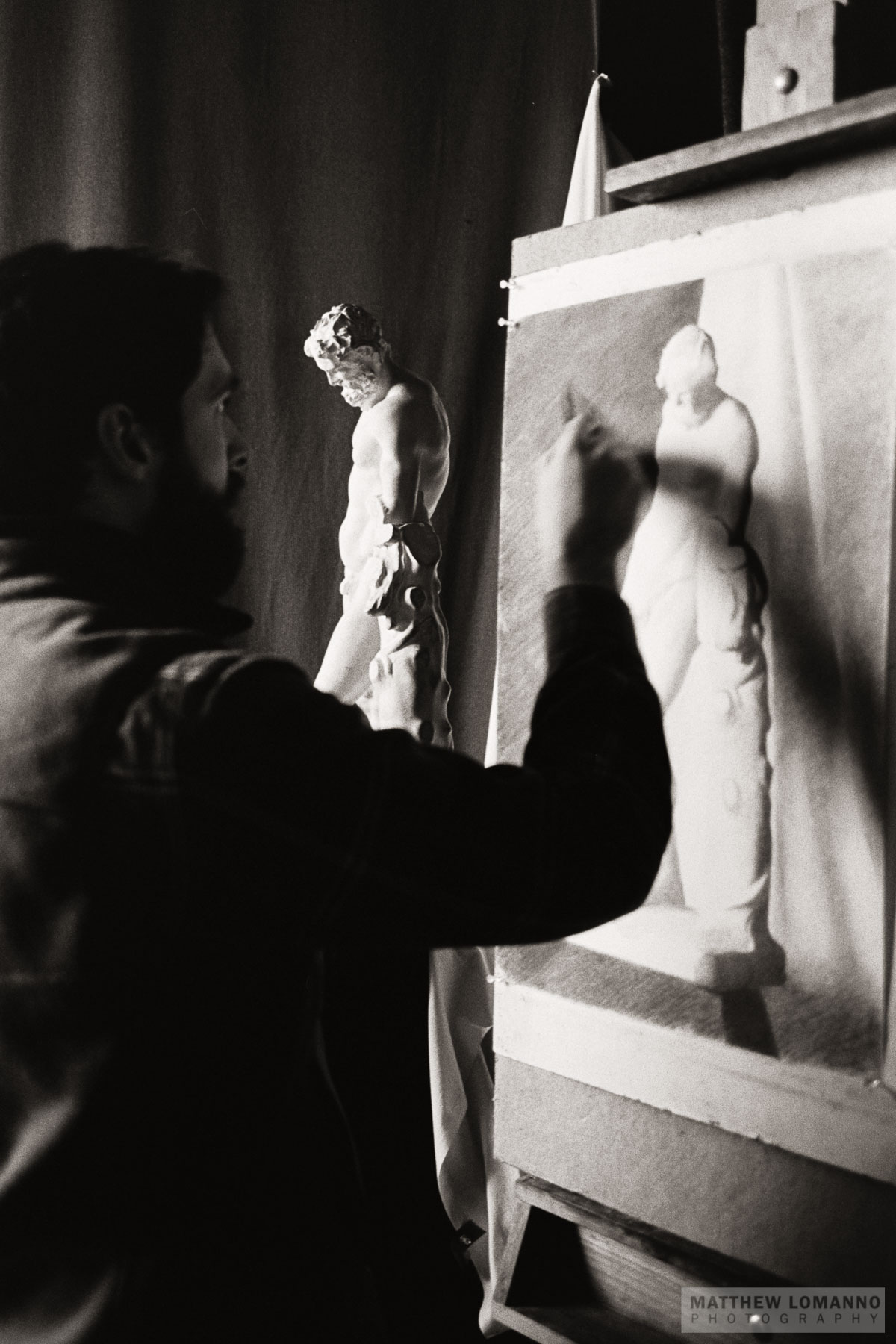

Observing the process of another artist—even in as mundane an activity as building temporary exhibition staging for the actual artwork—provides nearly endless fascination for me. It's a reminder that the habit of making at any stage of mastery is not pre-determined or even simple; it demands practical intelligence, the ability to judge the particulars of the object and what it needs, and how to achieve it. To make objects well requires time and practice such that a habit forms, so that when new situations present themselves, the ability to solve them is readily (and literally) at hand. Making art is, to a great degree, solving the problem of creating a whole, integral object.